Today is the 32nd anniversary of my mother’s death. I’ve debated whether or not to write about it on the blog for the past 36 hours or so. I am and have been deeply reluctant to write about her – I don’t want to seem mawkish or significant. And I sure don’t want anyone’s sympathy – I’ve been blessed in a multitude of ways. But I write anyway, because so much of who I am as a music person is from her – both in life and death.

My mother, Gerda Pastor, was born in 1931, in a little village called Nowy Targ, in the southern part of Poland, near the Czechoslovakia border. Her father, Max, was a  contractor who bought various foodstuffs in the Polish farmland, and then sold them to Polish army posts. He had been an officer in the Polish Army during World War I, and he built upon those contacts to create a successful business. Max was a gruff man, and while loving, the real warmth in the house came from my grandmother Bronia, who my mom adored. She also had an older sister, Helene, who she had an up and down relationship with.

contractor who bought various foodstuffs in the Polish farmland, and then sold them to Polish army posts. He had been an officer in the Polish Army during World War I, and he built upon those contacts to create a successful business. Max was a gruff man, and while loving, the real warmth in the house came from my grandmother Bronia, who my mom adored. She also had an older sister, Helene, who she had an up and down relationship with.

My grandfather knew by 1938 that there was no future for Jews in Poland. Anti-Semitism was all encompassing in Poland – my aunt told me years later that it was “everywhere you went.” The epithet “Dirty Jew” was commonplace and accepted at all levels of Polish society, and it followed my family, and all Jews everywhere. So they decided to get out. My grandmother had relatives already in New York, and they agreed to provide a sponsorship so they could attain visas. The process was ongoing in September of 1939, when Hitler invaded Poland.

My grandfather had managed to get American dollars in anticipation of leaving Poland, and with those, he proceeded to bribe their way out of Poland. Carrying as little as possible (what survives are some photos and a Candelabra that is at my father’s house), they got one of the last trains out of Warsaw before it fell to the Germans. They traveled to Romania, and then to Yugoslavia, where they got on the S.S. Rex, which sailed for New York and arrived November 15, 1939 (ironically, my day of birth, 31 years later). My mother was eight years old. Much of their family was still in Poland, and would eventually be murdered in Auschwitz, a fact that haunted my mother until her dying day.

Settling at first in the Bronx, and then in Washington Heights, my family began to adjust to life in America. My grandfather went to work as a dishwasher in the luncheonette that was owned my grandmother’s relatives, and did so without complaint. Then he became a line cook, and eventually, he owned his own dairy restaurant. There was no “English As A Second Language” type of program in the school system back then, so my mother and aunt (my aunt was 14) entered school without speaking a word of English. Within 6 months, my aunt says, they both could communicate passably in English. They adjusted.

What is important to know about my mother is that she was exceptionally beautiful, and her beauty gained her entry into a glamorous and sophisticated world. Men wanted to wine her, dine her, teach her, etc. (Emphasis on the “etc.”) She came to have a love affair with culture – film, music (especially opera), and fine art. She became a stylist, and she also wrote for several New York based art magazines as well acting as an agent for Vincent Cavallaro, who would later become my Godfather.

What is important to know about my mother is that she was exceptionally beautiful, and her beauty gained her entry into a glamorous and sophisticated world. Men wanted to wine her, dine her, teach her, etc. (Emphasis on the “etc.”) She came to have a love affair with culture – film, music (especially opera), and fine art. She became a stylist, and she also wrote for several New York based art magazines as well acting as an agent for Vincent Cavallaro, who would later become my Godfather.

She absolutely adored New York, and was the quintessential New Yorker – smart, sophisticated, sexy, urbane, and in possession of what my father later called, “a very wonderful and timely streak of vulgarity.” She dressed uber-stylishly. I’m not sure I ever saw her wear a pair of jeans. Dresses or slacks. And always high heels. She spoke several different languages and traveled often – to Italy (on several occasions), France and Israel (she was an intensely devout Zionist). Later on after I was born and she was in her 40’s, a male friend of a neighbor of ours said upon meeting her, “Oh, you’re the Femme Fatale from next door!” She batted her eyes at him – she loved it.

She met my father through her work in June of 1966. He was running a company that  manufactured womens shoes, belts and handbags, and she came to consult as a stylist. My father fell in love with her at first sight. “From the moment I saw her until the day she died,” he told me after she was gone, “there was no one else.”

manufactured womens shoes, belts and handbags, and she came to consult as a stylist. My father fell in love with her at first sight. “From the moment I saw her until the day she died,” he told me after she was gone, “there was no one else.”

When my father proposed, my mom had a few conditions. One of which was to have a child. My dad already had two kids and wasn’t keen on another, but my mom said she wanted to bring a Jewish child into the world that would replace the Jews that had been killed in the Holocaust. He accepted her conditions, and they married in November of 1968. Two years later I was born.

What I remember most about her in those years was her warmth. It was enveloping. When she was joyful, she could light up a room, and her laugh came from deep down within her, a soulful laugh. (My father loves to tell the story of how when they saw Mel Brooks’s “The Producers” in 1968, my mother the Holocaust survivor laughed so hard during the “Springtime For Hitler” scene that she peed in her pants.) She was physically demonstrative, generous with hugs and kisses for all.

She became devoutly religious as she got older, and I can remember how she would light the candles every Friday night to usher in the Sabbath. She would cover her eyes and say the prayer, and in those moments, she seemed almost taken by the spirit. I can see now that she was communing with something – maybe God, maybe the memories of Poland, or maybe just a spirit that she was attuned to. When she would tuck me in at night, we would always sing the “Shema” together, and it was done with an immense amount of love, but with more than a hint of sadness in there too. I didn’t know it then, but it was my first introduction to soul.

Her sadness became a real darkness at times. For whatever reason, she took the burden of the deaths of six million Jews upon her in some fashion, and it led her to drink. My dad told me well into my adolescence that I once asked him, “Why does Mommy act so different at night then she does during the day?” He traveled a lot for work then, so her drinking scared him to death, as she was responsible for looking out for me. It scared me too. I knew she loved me a lot, but the darkness she was enveloped in made her seem unreachable to me at times, and like all little kids, I  blamed myself. And then I got angry and I diminished her in my mind. Every night when my dad would walk in the door, I would be thrilled – it was though the cloud above the house lifted, and I felt completely safe again.

blamed myself. And then I got angry and I diminished her in my mind. Every night when my dad would walk in the door, I would be thrilled – it was though the cloud above the house lifted, and I felt completely safe again.

I don’t want to make too much of her drinking. It was there and it happened, but we were a very happy family. I was very happy. I never wondered for a second whether my parents loved me. I could feel their adoration. And I adored them.

Saturday, March 19, 1977 started as a gorgeous, brilliantly sunny day. It had snowed several inches the day before, severely enough that they shut my 1st grade class down about an hour or two after we had arrived. I watched my usual Saturday morning cartoons – The Bugs Bunny and Roadrunner show, followed by the Shazam and Isis hour on the little black and white TV in my room, played outside in the snow, and then got dressed.

At around 1pm we left in my father’s rust colored Dodge Dart to go to the library. He drove, I sat in the passenger’s seat so I could be his co-pilot, and my mom sat in the back seat. We were all in good moods. None of us wore seat belts. A few minutes after 1pm, we were traveling through an intersection when we were struck at full speed by another car that ran a blinking yellow light. We spun out and crashed into a telephone pole.

I remember vividly looking to my left, and seeing my father moaning and writhing, his eyes closed, in obvious agony. His moaning was an unbearable and frightening sound, but I was so disoriented that everything occurred to me in the moment as surreal. I had slammed stomach first into the glove compartment, but was strangely not in much pain. I was just scared, stunned and in shock. I heard sirens arrive quickly, and a policeman emerged to help me get out of the car. When he pulled me out, I turned to the right and saw my mom, unconscious, her head resting against the right window, a trickle of blood coming down her ear. I took the policeman’s hand and was led to a waiting ambulance. There was a crowd of onlookers at the scene, the looks on their faces both horrified and concerned. I turned around one last time and looked at the car, twisted and mangled beyond recognition.

My father, fortunately, suffered relatively light injuries (a broken rib and a black eye), but my mom never regained consciousness. While I underwent surgery for a ruptured spleen that the doctors detected after shortly after arriving at the hospital, the doctors told my father that while I was going to be fine, my mom had suffered massive brain damage from her head slamming into the window at the moment of impact, and she wasn’t going to make it. They had to tell him three times before it registered. She died a little past midnight on Sunday, March 20, 1977.

Even now, 32 years after, I find it difficult to really be with the enormity of what happened that day. But obviously, one part of my life ended on that day, and another one began. I soon forgot what my mom’s voice sounded like, and I can’t recall it consciously, but there are times that I’ve dreamt of her (I like to call it “getting a visit from her”), and when she speaks, it’s her authentic voice. She’s there within me, always.

My love and appreciation for music, for literature, for art and beauty – that’s her. What I heard in soul music from the moment I first heard Otis Redding - that deep sadness along the irrepressible joy, sometimes apart, sometimes entwined – well, that’s an experience of life that I understood, and understood young, probably too young. Soul music, at its best, is an acknowledgment of the harshest blows that life can give, coupled with an indominitable resiliency and will to keep going.

That will to keep going despite it all is why Springsteen’s music has meant so much to me, why the line “It ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive” from “Badlands” is one that never fails to move me to the core of my being. And it’s why I have so little listening of much of the post-modern music (yes, I’m talking to you, indie rock) that is at the vanguard of music today, so much of which is more head than heart, that takes its risks in the realm of form instead of emotion, revels in distance as opposed to connection, that in its cool, drains much of the joy out of song and performance.

When I’m in the studio with an artist or when I’m writing about a piece of music that I love and want you and everyone else to love and appreciate, that’s my mom within me. And it’s how I do my best to honor her memory, and keep her being alive. My mother used to quote a line from Puccini's Tosca, which declares, “I lived for art and I lived for love.” What else are you going to live for?

Download: Louis Armstrong - "West End Blues"

Download: Bruce Springsteen - "Across The Border" 11/26/96, Asbury Park, NJ

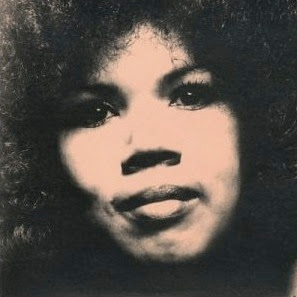

About six years ago I was in Tower Records (R.I.P.), browsing for albums, and saw a CD with a woman's face filling the cover, a soulful looking face, obviously a photo from the past. I picked up the CD, titled Candi Staton, and looked through the song titles, most unfamiliar to me, except for a few songs I knew by other artists, such as "In The Ghetto." I was about to put the CD back when the person standing next to me said, "If you like soul music, you need that CD."

About six years ago I was in Tower Records (R.I.P.), browsing for albums, and saw a CD with a woman's face filling the cover, a soulful looking face, obviously a photo from the past. I picked up the CD, titled Candi Staton, and looked through the song titles, most unfamiliar to me, except for a few songs I knew by other artists, such as "In The Ghetto." I was about to put the CD back when the person standing next to me said, "If you like soul music, you need that CD."